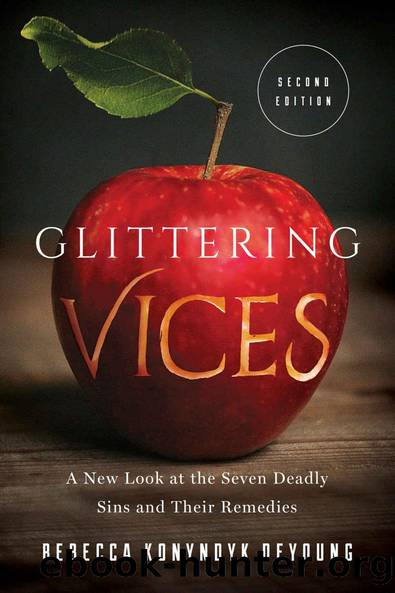

Glittering Vices by Rebecca Konyndyk DeYoung

Author:Rebecca Konyndyk DeYoung [DeYoung, Rebecca Konyndyk]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Spiritual Formation, Deadly Sins, REL062000, REL012120, REL067070

ISBN: 9781493422166

Publisher: Baker Publishing Group

Published: 2020-06-01T15:00:00+00:00

Target Practice

Letâs return to Aquinasâs more moderate line on anger for a moment. If we grant that it could be a healthy emotion as well as a hellish habit, something we could feel and express either well or badly, then what would mark the difference between good anger and the vice of wrath?

Aquinas analyzes anger as an emotional force of resistance and a complex emotion. Its open antagonism toward whatever injures or threatens is driven by a passionate devotion to the good. Appropriate anger expresses the desire to enact âwhat is required for justice to be done.â19 When things go well, correcting injustice is our worthy goal. Any punishment of an offense (an evil) may be sought only for the sake of this good. (By contrast, willing evil as such to another person counts as hatred, the opposite of love.) Note that wrath is a peculiarly human sin, since its disorder requires that we have a sense of justice to be twisted. In an ironic testimony to the power of this good, the wrongly angered and wrathful person also perceives his or her end as just or works hard to rationalize it as such. In both cases, the desire for justiceâwhether real or apparentâstrongly motivates us; our anger marches under its banner. Recall that the capital vices begin with great goods, which, when pursued wrongly or excessively, tend to produce much other sin. Thus, the excellence and desirability of its self-proclaimed good end make wrath a capital vice, as does its âimpetuosity,â since wrath easily incites us to many other sinful actions by its force.

We also experience the passion of anger physically. Its effect on our bodies makes us alert and ready for action. Anger covers the âfightâ portion of our fight-or-flight response to danger, evil, and difficulty. As such, it can be our ally in action, by helping us deal with both inner and outer difficulties that could discourage us from pursuing whatâs right. Someone who would otherwise be too shy may need the push of anger to stand up and speak out when he needs to defend the downtrodden. Someone who would otherwise feel too weak may fight beyond the limit of her power if anger fires her spirit. A complacent congregation may need anger to lift it out of indifference and mobilize it into just advocacy.

But if anger makes us ready to fight, then we must âfight the good fightâ in order to avoid angerâs turn toward vice. This means fighting for a good cause and fighting well. Our anger must serve the cause, not the other way around. Venting the emotion is not itself the point, even if we succumb to the common mistake of trying to dissipate anger by letting off some steam. With all sins against temperanceâincluding wrath, lust, and gluttonyâAquinas observes (and contemporary psychological studies confirm)20 that, like two-year-olds, the passions get more unruly and harder to control the more we indulge them.21 But merely suppressing anger isnât the point. The goal of restraining or âtemperingâ anger is to keep reasonâs judgment clear.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Christian Ethics by Wilkens Steve;(860)

Christian Ethics for a Digital Society by Kate Ott(781)

Fearfully and Wonderfully Made by Philip Yancey & Paul Brand(774)

God and the Multiverse by Victor J. Stenger(679)

Numbers by Ronald B. Allen(642)

How to Read Slowly by James W. Sire(618)

Christian Ethics: An Introduction to Biblical Moral Reasoning by Wayne Grudem(602)

The City of God by Saint Augustine & Marcus Dods(597)

Morality by Jonathan Sacks(570)

Monastic Archaeology by Unknown(569)

The Technological System by Jacques Ellul(553)

Amish Grace by Donald B. Kraybill & Nolt Steven M. & Weaver-Zercher David L(537)

Death of the Doctor by Unknown(532)

The Disabled Church by Rebecca F. Spurrier;(528)

Jesus: A New Vision by Whitley Strieber(524)

Children of Lucifer; The Origins of Modern Religious Satanism by Ruben van Luijk(513)

Critical Writings by Joyce James;(503)

Redeeming Sociology by Vern S. Poythress(489)

The Church in the Early Middle Ages by G.R. Evans(481)